Emotionally intelligent investing: How to make smarter decisions

In traditional economic theory, investors are assumed to be “rational”. This means that given access to information about the market, investors will always use this to make the most logical decision. In reality however, this is often found to be untrue. One of the biggest struggles investors face — especially in today’s market — is an inability to tune out the “noise” and make successful decisions based on logic, not emotion. In this blog, we will explain some of the common pitfalls investors face and what you can do to become a more emotionally intelligent investor.

Distancing

As investors, we sometimes make poor decisions because our emotions prevent us from seeing the obvious solution. Thinking from a third-party point of view reduces emotion-driven decisions, which can be an effective antidote against the endowment effect.

In the book Misbehaving, Richard Thaler, a behavioural economist, explains that his friend purchased bottles of wine long ago for $10, which are now worth over $100. He drank them on some special occasions but would never pay $100 to acquire them. That’s the endowment effect: When we already own an object, we would demand more to give it up than we would be willing to pay to acquire it.

For example, if you own a stock for many years that has done well in the past, it can be hard to decide what to do when the company’s future direction becomes less rosy than you’d expected. Therefore, imagining what someone else might do in your situation can help you look at the investment more objectively while avoiding confirmation bias. This is known as “distancing”.

Distancing can also be useful when you’re tempted to get into an exuberant market, or you’re crowding around the exit door in a market panic. Most investment mistakes happen during the buy or sell stage, caused by external factors such as market volatility. We tend to rely on what Daniel Kahneman called System 1 — fast, instinctive, and emotional thinking — during these situations. Distancing prevents that by letting our System 2 thinking take control, which is slow, deliberative and logical thinking that reduces the odds of making mistakes.

Ulysses contract

In Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, Odysseus, the legendary Greek king of Ithaca, is aware of the danger of passing the island of the Sirens. Sailors who get bewitched by the Siren song will steer towards the shore and crash to their death. To avoid that, Odysseus told his sailors to tie him to the mast and cover their ears with beeswax so they could sail past the island unaffected by the Siren song.

The Ulysses contract is a freely made decision that is designed and intended to bind oneself in the future. It is a form of precommitment where you commit to doing certain things in advance.

For example, setting up an automatic regular investment plan is a precommitment. It reduces the chances of making poor decisions because by automating the process, it saves you from having to make and remake the same decision. You know that a fixed portion of your salary will go into an investment before you get to spend it on other things.

An investment checklist is also a Ulysses contract. If you have a checklist you have to go through before you hit the buy or sell button, that is likely to reduce your chance of making poor impulse decisions.

The Ulysses contract is an exit plan as well. Most people get into an investment without knowing when or under what circumstances they should sell. As a result, the sell decision often gets influenced by the share price’s direction. This is why almost everyone does the opposite of ‘buy low, sell high’.

The Ulysses contract can also be in the form of setting a limit of how much to put into a stock to avoid overinvestment, e.g. “I’ll put no more than $10,000 into this stock”. Or it can be a fixed timeframe like “I’ll sell this stock after 12 months regardless of the price”. These contracts prevent us from holding onto a position for far too long simply because the price keeps breaking new highs, or from hoping a value trap stock will someday return to its purchase price.

Tripwire

David Lee Roth is the lead singer of Van Halen, an American rock band. In Van Halen’s 1982 world tour, the band had an unusual request stated in their contract: M&M’s (WARNING: ABSOLUTELY NO BROWN ONES). When David Lee Roth arrived backstage, he would make sure there were no brown M&M’s in the bowl.

This turns out to be a smart idea. With a contract as thick as hundreds of pages, it’s impossible to check every single setup to make sure the concert organiser followed all the setup procedures. So no brown M&M’s would act as a tripwire to find out whether the organiser has overlooked some important aspects of the setup.

A tripwire makes you stop and think. The two common tripwires in investing are:

- “If the market is closed for the next 10 years, would I still buy it?”

- “Would I buy more if the stock falls by 50% tomorrow?”

Our brain is like that hundred-page contract — it’s hard to know what’s going through our mind when we make a decision. So these tripwire questions are like the brown M&M’s that tell you whether you’ve missed something important in your investment process.

When Warren Buffett encourages investors to write down their reasons on a piece of paper, i.e. “I wanted to buy (numbers) of (stock) at (price) because….”, that’s a tripwire. It makes you stop and think. If you find yourself staring at the blank paper for too long, then that’s a big red flag. Abort the buy immediately.

A more controversial tripwire concept is brokerage fees. Nowadays, many online brokers offer zero trading fees. What if you get one that charges $200 per trade? That would make you think long and hard before you make a trade. Just as you’ll find more drunk people at a bar that offers free-flowing alcohol, there will be more rampant trading when the cost to do so is zero. The $200 brokerage fee has a similar psychological benefit to taking a cold shower on a winter morning: It clarifies the thoughts and improves decision quality. This benefit could potentially outweigh the short-term discomfort of losing $200 (or numbness on the face).

10/10/10

Before you make a decision, ask yourself the following: “What are the consequences of my decisions in 10 minutes? In 10 months? In 10 years?”

In the book Thinking in Bets, Annie Duke describes how 10/10/10 can help us make better decisions. She writes, “Bringing our future self into the decision gets us started thinking about the future consequences of those in-the-moment decisions. We are more likely to make choices consistent with our long-term goals when we can get out of the moment and engage our past and future-selves.”

We tend to make bad investment decisions due to short-termism; too much focus on what’s happening at the present, especially when you follow the market. Humans are governed by a simple rule: Seek pleasure and avoid pain. We sell during a market crisis because it is painful to watch our investments go up in smoke. This is also called temporal discounting: We favor our present self at the expense of our future self.

The solution here is to shift our focus from the present to the future by thinking about what are the consequences of our actions 10 months from now and 10 years from now. This changes how we feel about the situation and the decision we are about to make.

This is not to say selling when the market is down is always the wrong decision, of course. Investment is all about opportunity cost. But the key point is that when we take into account the long-term implication of our actions, we are likely to make a better decision than when we are inundated by what’s happening right now.

Invert

“Invert, always invert!” is Charlie Munger’s advice on making better decisions.

Inversion is a way to flip your thinking by thinking backward and forward. If you want to make good decisions, think of ways to mess things up and avoid just that. If you want to make money in the stock market, ask “How do people lose money?” and do the opposite.

Want a company that thrives in hard times? Then, how do you make a company go bust? You saddle it with lots of debt, put it in a cyclical, commoditised industry with a high fixed cost and high exit barrier, and install management who have incentives to fatten their own pockets.

Should I buy this stock? Think of all the reasons that will make you sell it, and only buy it if you still find the stock attractive.

How can you have better self-control and be less emotional in the market? That’s hard to answer. An easier question would be “How do you make someone panic?” Well, you keep them in the dark so they are unprepared and get surprised easily, make them sleep-deprived, and overwhelm them with information.

At the end of the day, it’s important to go with your gut (or the advice of a trusted financial professional, if you have one). But if you want to make smarter investing decisions, it’s also important to recognise where emotions might be clouding your judgement, and do your best to remove them from the equation.

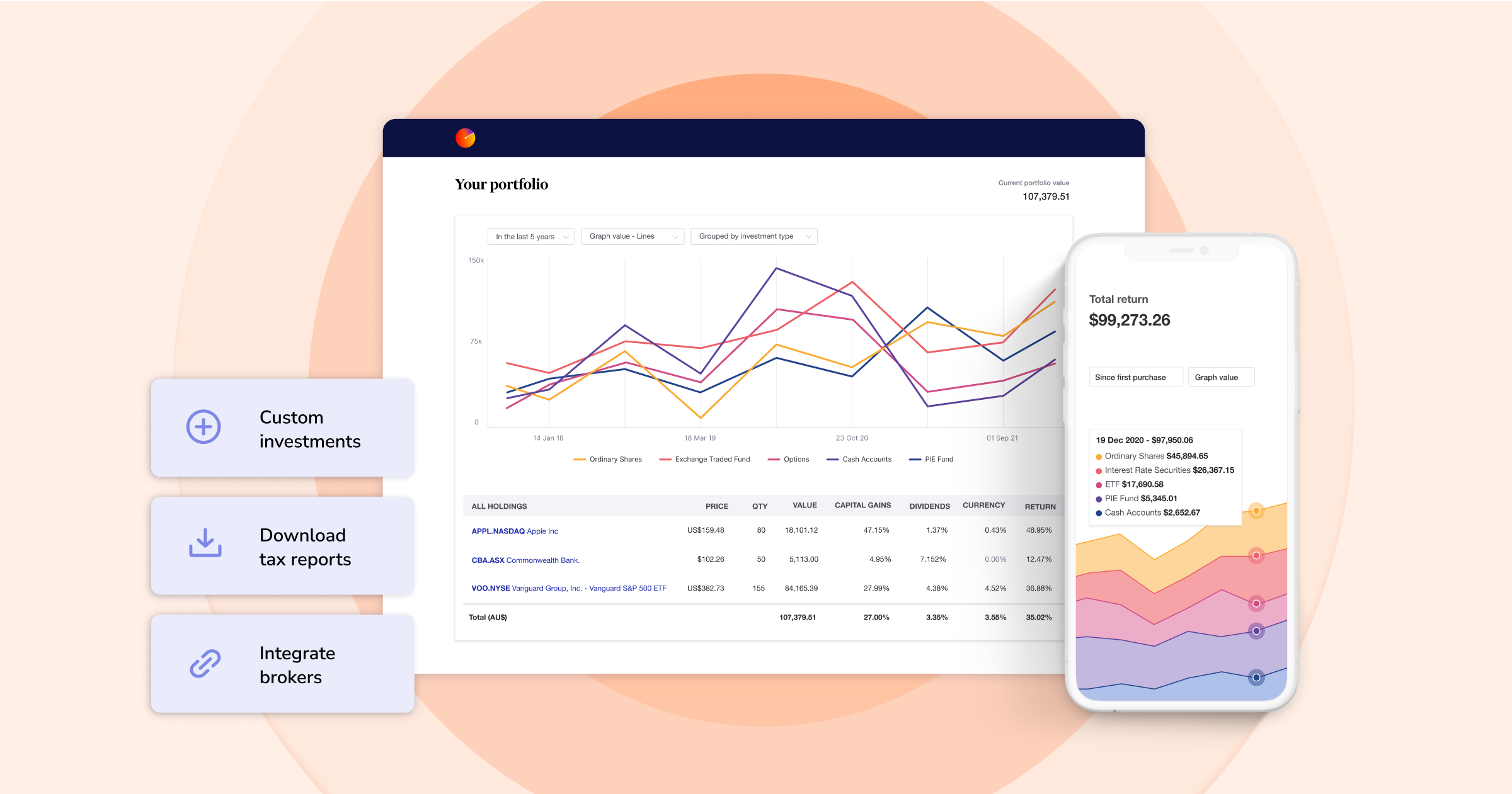

Become a smarter investor with Sharesight

Join hundreds of thousands of self-directed investors using Sharesight to track the performance of their investments and get the insights they need to make smarter decisions. With Sharesight you can:

- Track all of your investments in one place, including stocks, ETFs, mutual/managed funds, property and even cryptocurrency

- Automatically track your dividend and distribution income from stocks, ETFs and mutual/managed funds

- Run powerful reports built for investors, including performance, diversity, contribution analysis, exposure, future income, multi-period and multi-currency valuation

- See the true picture of your investment performance, including the impact of brokerage fees, dividends, and capital gains with Sharesight’s annualised performance calculation methodology

Sign up for a FREE Sharesight account to get started tracking your investment portfolio today.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a specific product recommendation, or taxation or financial advice and should not be relied upon as such. While we use reasonable endeavours to keep the information up-to-date, we make no representation that any information is accurate or up-to-date. If you choose to make use of the content in this article, you do so at your own risk. To the extent permitted by law, we do not assume any responsibility or liability arising from or connected with your use or reliance on the content on our site. Please check with your adviser or accountant to obtain the correct advice for your situation.

FURTHER READING

Why Strawman’s founder uses Sharesight to track performance and tax

We spoke with Andrew Page, founder of Strawman.com, about how he uses Sharesight to track his portfolio and how it benefits investors.

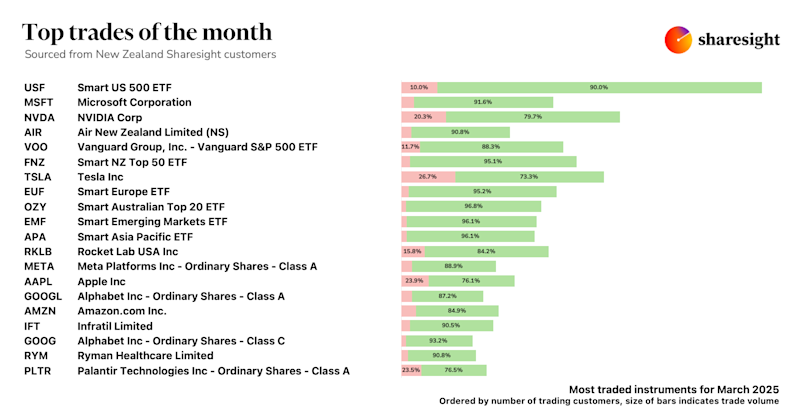

Top trades by New Zealand Sharesight users — March 2025

Welcome to Sharesight’s March 2025 trading snapshot for New Zealand, highlighting the top trades made by New Zealand Sharesight users.

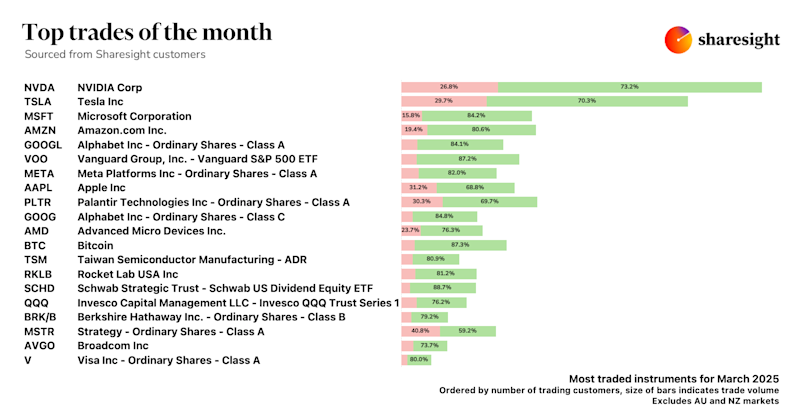

Top trades by global Sharesight users — March 2025

Welcome to the March 2025 edition of Sharesight’s trading snapshot, where we review the top trades made by Sharesight users worldwide.